Perinatal anxiety

Perinatal anxiety is very common. In a recent Australian study, one-fifth of women assessed during late pregnancy and reviewed at 2, 4 and 6–8 months after the birth had an anxiety disorder (approximately two-thirds with co-occurring depression) and almost 40% of women with a major depressive episode had a co-occurring anxiety disorder.

There are a number of different types of anxiety disorders. The most common conditions that arise in pregnancy or after birth are detailed below:

| Type of anxiety disorder | Description |

|---|---|

| Generalised anxiety disorder (GAD) | Feeling worried about perinatal issues on most days over a long period of time (e.g., six. months). Some common topics of worrying include: - The infant’s wellbeing, safety and possible threats (e.g., SIDS) - Getting one’s life in order, having everything planned and sorted - Constant worry about how they will cope - Breastfeeding worries (e.g., had the baby had enough milk, will their milk supply run out) - Keeping the household chores attended to - How they will manage work and parenthood - How to give their other children enough attention while meeting the needs of the new infant |

| Panic Disorder | Frequent attacks of intense feelings of anxiety that seem like they cannot be brought under control. These attacks can occur when: - Thinking about leaving the house with their new baby - Attending mother's groups - Worrying about sleep and settling issues - When transitioning their infant to solid food (fear of choking) |

| Social phobia | Involves an intense fear of criticism, being embarrassed or humiliated, even in everyday situations. Some common examples in the perinatal context include: - Invasion of their personal space - People touching their baby - Worries about involvement of friends and family and different opinions on baby’s needs - Infant drawing attention to them publicly - Worries about mother’s groups - Worries about people judging their parenting (e.g., crying baby in supermarket) |

| Specific phobia | Fearful feelings about a particular object or situation. This can commonly include vomiting (babies often vomit), body changes (eating disorder traits/anxiety), death of a loved one, coprophobia |

Antenatal anxiety may occur in response to fears about aspects of the pregnancy (e.g. parenting role, miscarriage, congenital disorders) or as a continuation of a pre-pregnancy condition and/or comorbidly with depression. Higher levels of self-reported anxiety or anxiety disorder in pregnancy increase the risk of depression postnatally.

Anxiety disorders can have significant effects on the health and wellbeing, not only of the mother but also her partner and other children. The latest research also reveals that anxiety disorders can have a negative impact on the growth and development of the foetus/baby, so early detection and intervention is paramount.

In many instances, anxiety symptoms are not recognised, as they are often viewed in the context of pregnancy or adjusting to the baby. In addition, high levels of stigma may prevent women seeking help.

Symptoms of perinatal anxiety

There are many types of anxiety disorders. While the symptoms of perinatal anxiety disorders are different, women who have symptoms of an anxiety disorder may experience:

- Anxiety or fear that interrupts thoughts and interferes with daily tasks

- Panic attacks — outbursts of extreme fear and panic that are overwhelming and feel difficult to bring under control

- Anxiety and worries that keep coming into the woman’s mind and are difficult to stop or control

- Constantly feeling irritable, restless or “on edge”

- Having tense muscles, a “tight” chest and heart palpitations

- Finding it difficult to relax and/or taking a long time to fall asleep at night

- Anxiety or fear that stops the woman going out with her baby

- Anxiety or fear that leads the woman to check on her baby constantly

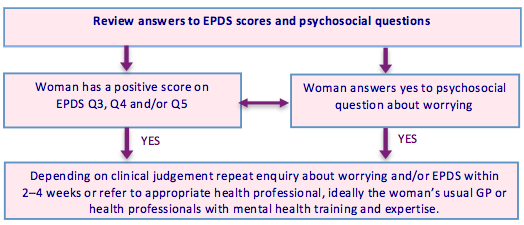

The psychosocial question on “worrying” and Questions 3, 4 and 5 of the Edinburgh Postnatal Depression Scale (EPDS) reflect some of these symptoms.

Assessing women for perinatal anxiety

Assessing women for possible perinatal anxiety involves considering their answer to the psychosocial question on “worrying” and identifying possible symptoms using Questions 3, 4 and 5 of the Edinburgh Postnatal Depression Scale (EPDS).

About the EPDS

The EPDS is a questionnaire developed to assist in identifying symptoms of depression. It is also useful in identifying symptoms of anxiety. The EPDS is not a diagnostic tool; rather it aims to identify women who may benefit from follow-up care, such as mental health assessment, which may lead to a diagnosis based on accepted diagnostic criteria (DSM-V or ICD-10).

Translated versions of the EPDS have been validated in some languages.

How often should the EPDS be completed

All women should complete the EPDS at least once, preferably twice, in both the antenatal period and the postnatal period (ideally 6–12 weeks after the birth).

The non-diagnostic nature of the EPDS, its purpose and the fact that it relates to the previous seven days (not just that day) should be clearly explained.

When follow-up care is required

Follow-up for further assessment for anxiety disorders may be needed if a women’s answer to the psychosocial question on “worrying” or her scores on Questions 3, 4 and 5 suggest possible symptoms of anxiety.

Note: Follow-up is also needed if the total score is 13 or more or if a woman has a positive score on Question 10 (self-harm).

Management of perinatal anxiety

Support and early intervention for women experiencing distress or anxiety symptoms may help to prevent more serious mental health problems from developing. Depending on the severity of a woman’s symptoms, management of perinatal anxiety may involve a combination of psychosocial support, psychological therapy and pharmacological treatment. Appropriate responses to assessments and clinical judgement are fundamental to decision-making about management.

1. Psychosocial support

Psychosocial interventions used as preventive approaches or as part of management of anxiety includes non-directive counselling, psychoeducation, such as our free e-guide Ready to COPE, and peer support.

Women may also benefit from being given information about options for support in their communities (e.g. parent education groups, support groups, playgroups) and suggestions for where to seek practical support with tasks like cooking, cleaning and taking care of the baby, or any older children (e.g. family, friends, neighbours or community services).

2. Psychological therapies

The range of psychological therapies that are effective in treating anxiety disorders at times other than in the perinatal period would also be expected to be effective in the perinatal period, as the disorders differ little from disorders among non-pregnant women in both their presentation and course.

3. Pharmacological treatments

During pregnancy, use of selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs) can be considered, as there is no evidence for a consistent pattern of birth defects. Tricyclic antidepressants (TCAs) can also be considered, especially if they have been effective previously, but should be used with caution due to the risk of overdose.

Both SSRIs and TCAs can also be safely used during breastfeeding. Short-term use of short-acting benzodiazepines may be considered while awaiting onset of action of SSRIs.

More detail on the safety and effectiveness of pharmacological treatments is included in the National Perinatal Mental Health Guideline developed by COPE. Guidelines for the use of antidepressants and benzodiazepines in the general population should be consulted.

Key points to remember

Some things to remember when assessing and managing anxiety in the perinatal period are:

- There is evidence to support use of EPDS in detection of anxiety: Although the EPDS was specifically developed to detect symptoms of depression, there is evidence to support its use in the detection of symptoms of anxiety, taking into consideration the woman’s scores on questions 3, 4 and 5, her answer to the psychosocial question on “worrying” and applying clinical judgement.

- The EPDS can be administered verbally: While the EPDS is a self-report tool, it may be appropriate for it to be administered verbally in situations where there are difficulties relating to language or literacy, cultural issues or disability.

- Explain the purpose of the assessment: Before the EPDS is administered, women need clear explanation of the purpose of the assessment (including that it is part of normal care and will remain confidential) so that they can provide informed consent. If a woman does not consent to assessment, this should be documented and assessment offered at subsequent consultations.

- Decision-making should be based on woman’s preferences and clinical judgement: Decision-making about the need for and type of follow-up mental health care should take into account these factors.

- Not everyone needs or will want further monitoring or mental health assessment: Providing information and encouraging continuing contact with an appropriate health professional can support women to seek further assistance if indicated.

- GPs can provide continuing mental health care management: Ideally, a woman’s regular GP will provide continuing mental health care in the perinatal period. However, not all women have access to this type of care or choose it when it is available. Assist women to identify a health professional with the skills, knowledge and cultural competence to provide appropriate ongoing care.

- Continuity of care is an important aspect of effective care: It is important to document all assessments and share relevant information with the next health professional providing care to the woman (e.g. a midwife passes information to maternal and child health nurse).

- Mental health can be subsidised under Medicare: To access Medicare counselling items, a GP needs to provide a letter of referral for pregnancy support counselling or develop a mental health treatment plan with the woman for more formalised mental health treatment. The GP then refers to a mental health care professional either through the Better Access Scheme. For further information about available support under Medicare click here.

Fact sheet for health professionals

- Download our Perinatal Anxiety Factsheet for Health Professionals